Consent is one of the trickiest parts of the General Data Processing Regulation (GDPR). Consent under the GDPR is not easy, especially in practice and when you start looking at it from a perspective of specific personal data processing activities whereby consent turns out to be the only or most appropriate legal basis for the lawful processing of personal data.

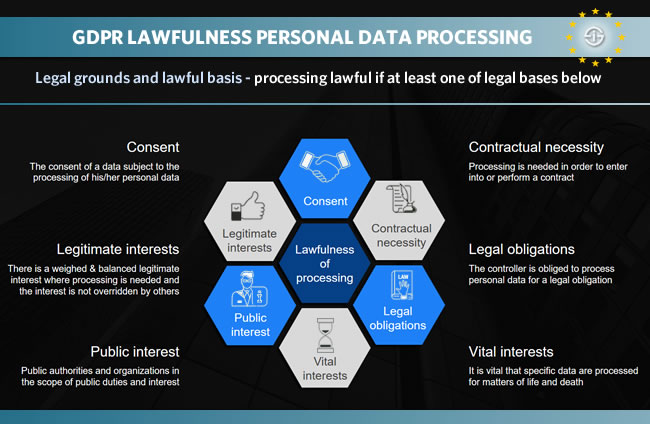

We’ve covered those legal grounds under which you are allowed to collect/process personal data before but mention it here right away too as one of the GDPR myths remains that only when consent is given by the concerned natural person, a.k.a. data subject, you can process his/her data. This is wrong.

When consent is the legal basis for lawful processing data subjects need to be clearly informed about their rights to withdraw consent and need to be able to do so easily if desired

There is also a difference between consent and explicit consent, although the line is thin. Lastly a reminder for companies outside of the EU that process personal data of EU citizens (and processing is close to everything you can imagine regarding the data subject’s personal data): the GDPR and the rules of consent apply to you as well.

Consent under the GDPR is a tricky matter for many reasons. The main reason has a lot to do with the scope of the GDPR and the nature of consent.

The GDPR gives data subjects control over their personal data, consent in the GDPR gives even more control

The GDPR is the EU’s new legal framework for privacy and personal data protection. It catches up with the digital reality, adapts to a data-driven digital transformation economy (why it matters for data controllers and for data processors across the globe), creates a common framework for all organizations and essentially puts back the control over personal data in the hands of people.

This means that organizations must think about how they deal with personal data and act to put that thinking into action, thereby looking at their current cybersecurity approaches.

HOWEVER, whereas the control over personal data is given back to people with privacy being a fundamental right and a range of new rights for people, CONSENT GIVES PEOPLE EVEN MORE CONTROL OVER THEIR DATA (we put it in capitals for a reason) on top of the essential data subject rights.

If you look at that from the organization’s viewpoint this means that, on top of the new rights which data subjects have and the organization needs to enable, with consent data subjects have even more rights and companies using consent have more duties and mechanisms to deal with them in place.

Can you use other options then consent? You sure can. In fact, for EACH data processing activity you should ask yourself what is the best legal ground. Is it consent? Is it another? HOWEVER, de facto there will always be personal data processing activities for which consent is the only/best option.

Consent and consent management

So, you need to understand consent under the GDPR. You also need to understand how to manage consent.

Consent management essentially covers the consent lifecycle from start to finish: from data collection and enabling data subjects to change or withdraw consent to deleting personal data whenever the purpose and duration of the data to which the data subject consented are finished.

Under the GDPR, consent requires a clear affirmative action and must be demonstrated by the controller

In practice that’s pretty hard. Moreover, once you start looking at solutions for consent management there are several platforms but those that also allow you to easily enable people (data subjects) to exercise their rights once you’re under the ‘regime’ of consent in the GDPR, such as that withdrawal of consent, are often high-end enterprise solutions that aren’t easy to understand or afford for smaller and medium businesses and even for large organizations come with challenges. Still, on top of consent management solutions which are part of sometimes very expensive compliance applications some are affordable for small and medium organizations too. Two examples of GDPR consent management platforms we covered are the OneTrust GDPR consent management platform and the Evidon GDPR consent solution.

Before starting to think solutions and tools, it’s key to have your consent mechanisms in place which also requires you to know where you need consent (what personal data processing activities), what the consequences and related duties are and how you will meet the numerous GDPR requirements in the scope of consent.

So, that’s where we start, with the various aspects of the definition of consent and then the meaning and impact of freely given, informed, specific, clear and active consent. Do note that consent is also omnipresent in the ePrivacy Regulation text as it was approved by the EU Parliament (‘the Lauristin Report‘).

A reminder of consent under the GDPR

As mentioned (also in other articles), consent is one of the six legal grounds for lawful processing whereby for each data processing activity there needs to be at least one of these six in place. You can see all six below.

Consent is probably the best known and most often mentioned but that doesn’t mean it is always the most appropriate one as said. Moreover, as said with consent as a legal basis come several duties and additional rights for data subjects that have consented to the processing of their data.

First, the definition of what consent is under the GDPR (as you can read it in the GDPR definitions in GDPR Article 4).

Consent is an unambiguous indication of a data subject’s wishes that signifies an agreement by him/her to the processing of personal data relating to him/her (note: in any given personal data processing activity) whereby that consent needs to be given in clearly defined ways which are those elements of the definition of consent that are further explored.

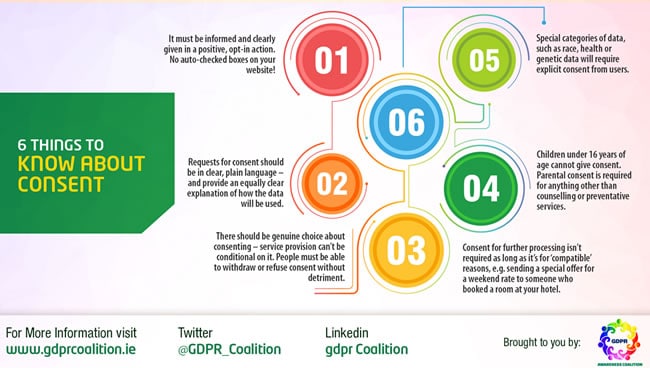

GDPR Article 7 sums up the essential conditions regarding consent (to be valid). In a nutshell:

- Consent needs to be freely given.

- Consent needs to be specific, per purpose.

- Consent needs to be informed.

- Consent needs to be an unambiguous indication.

- Consent is an act: it needs to be given by a statement or by a clear act.

- Consent needs to be distinguishable from other matters.

- The request for consent needs to be in clear and plain language, intelligible and easily accessible

We’ll cover them below, starting with a deeper drive into the first element, freely given consent.

Freely given consent under the GDPR

The fact that consent needs to be freely given is more than it seems once you start looking into what exactly freely given means.

We have, among others, the guidance of GDPR Recital 43 which mentions examples of when consent is not deemed freely given.

Freely given consent and free will versus the imbalance of power and conditionality

A first one introduces the notion of imbalance of power whereby a clear imbalance between the data subject and the data controller (the organization deciding on the purpose and scope of the personal data it processes or wants to process) in a specific case is such that it is unlikely consent was freely given.

Freely given consent implies real choice and is especially difficult or impossible when there is an imbalance between controller and data subject, when consent is conditional, when several purposes for processing are bundled, need to be separated and require consent for each purpose, and in case of detriment.

This is particularly the case when the data controller is a public authority (there are of course situations in which public authorities need to process personal data without freely given consent or consent as such).

The WP29 guidelines on consent reminds that an imbalance of power can also occur in the employment context (which doesn’t exclude consent in this context) and in other situations.

In general this is what the guidelines say about an imbalance of power and consent: “Consent will not be free in cases where there is any element of compulsion, pressure or inability to exercise free will”.

A second example in GDPR Recital 43 is a situation whereby it is not possible to give separate consent to different data processing operations, even if consent is appropriate in the individual case or if the performance of a contract or provision of a services depends on consent although the consent is not needed for the performance of the contract or the provision of the service. This introduces a second notion in the scope of freely given consent: conditionality.

In its fourth paragraph, GDPR Article 7 very clearly refers to freely given consent where it says that “when assessing whether consent is freely given, utmost account shall be taken of whether, inter alia, the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is conditional on consent to the processing of personal data that is not necessary for the performance of that contract”. With ‘inter alia’ meaning ‘among others’ this essentially means: don’t make consent a condition for all those cases (such as contracts and services) if it isn’t strictly needed because it will be deemed not freely given. That is the notion of conditionality.

A few of the main things to check in the scope of conditionality, the WP29 guidelines on consent remind, include 1) making sure the right basis for lawful processing is chosen, certainly in the context of a contract, 2) not merging several bases of lawful processing and 3) looking at the scope of the contract or service whereby ‘necessary for the performance’ needs to be interpreted strictly.

One can easily imagine cases where there is a clear imbalance between data subject and data controller (imbalance of power), there are ample of circumstances when consent is asked in the scope of a contract or service (conditionality) and/or where separate consent cannot be given (where we meet another notion; granularity).

De facto many organizations still connect the requirement of giving consent with the fact that the consumer gets something (or not) which obviously means consent is not freely given. By way of an example: an association of car drivers that offers the possibility to its members to get a replacement vehicle in the scope of breakdown assistance only if the drivers who want to get the replacement vehicle as part of their membership consent with the tracking of their data and monitoring of their driving behavior via telematics. In such a case consent is not the best approach and is not allowed as consent is not freely given.

Freely given consent: granularity, bundled consent and purpose

Those notions are essential elements. Although not explicitly mentioned in the text, the GDPR emphasizes the importance of really freely given consent.

GDPR Article 7 further makes sure to protect some of the points in Recital 43:

Although again not specifically mentioning ‘freely given’, in its second paragraph, Article 7 says that, when consent is given in the scope of a written declaration that also concerns other matters, the consent must be given in a way that makes is clearly distinguishable of these other matter is a very clear way and language. In other words: consent can’t be deemed freely given if, where it is needed, it is hidden in the declaration and/or not clear and, most of all, not distinguishable.

Consent is relevant when there is no better legal ground for lawful processing of people’s personal data, you can deliver upon providing them more control and choice over the way you process their personal data than the GDPR as such does and if you seek high levels of trust.

As mentioned in our article on the legal grounds for lawful processing, consent is given for one or more specific purposes and that notion of purpose is key as you can read in GDPR Article 6.

Moreover, consent cannot be ‘bundled’ and that is where the notion of granularity really plays: no consent to a bundle of processing purposes and granularity; instead: separation of the several purposes and consent per purpose.

Or as GDPR Recital 32 puts it: “Consent should cover all processing activities carried out for the same purpose or purposes. When the processing has multiple purposes, consent should be given for all of them”.

Comment from the WP29 guidelines on granularity and freely given consent: “If the controller has conflated several purposes for processing and has not attempted to seek separate consent for each purpose, there is a lack of freedom. This granularity is closely related to the need of consent to be specific…when data processing is done in pursuit of several purposes, the solution to comply with the conditions for valid consent lies in granularity, i.e. the separation of these purposes and obtaining consent for each purpose”.

Freely given consent: guidelines and example

Further clarifications in the GDPR text and in the consent guidelines of the WP29 (European Data Protection Board) are clear.

Control over personal data is in the hands of the data subject so when you ask consent don’t use any power or pressure to force the data subject (not just between public authorities and data subjects but also, for instance, between employers and employees or other relationships where there is a clear imbalance and one could feel forced), don’t hide things in contracts and make sure that the data subject has a real choice to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ without excuses whatsoever.

Quoting from the ‘Guidelines on Consent under Regulation 2016/679’ by the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party (guidelines which are often followed by supervisory authorities): “The element “free” implies real choice and control for data subjects. As a general rule, the GDPR prescribes that if the data subject has no real choice, feels compelled to consent or will endure negative consequences if they do not consent, then consent will not be valid”.

The guidelines of the WP29 on consent give an example that makes it more tangible and can make you imagine several similar ones.

The example concerns a mobile application allowing users to edit photos. However, it also wants to know the localization of the users by saying that the app needs to activate the GPS functions in order to do so, in order to be able to use the services offered by the app and in order to offer behavioral ads. As both the ads and the geolocalization aren’t needed for the functioning of the app (purpose, namely, photo editing), the consent of users isn’t considered freely given as it’s not needed for the provision of the service. Attention: this example is given by the WP29 in its guidelines and in the scope of consent as the legal ground for processing!

Moreover, “If consent is bundled up as a non-negotiable part of terms and conditions it is presumed not to have been freely given. Accordingly, consent will not be considered to be free if the data subject is unable to refuse or withdraw his or her consent without detriment. The notion of imbalance between the controller and the data subject is also taken into consideration by the GDPR”.

Freely given consent and detriment

So, essentially these quotes from the guidelines and the example cover the elements of freely given consent and the mentioned notions. In the last part of the quote, another element and notion regarding freely given consent is added, that of ‘detriment’.

The element of detriment first needs to be seen in the context of GDPR Recital 42, which doesn’t only mention the duty of the controller to be able to demonstrate that consent has been given (one of those additional duties if consent is the chosen legal basis for data processing) but, among others, also states at the end that “consent should not be regarded as freely given if the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment”.

In other words: as is stipulated in the first paragraph of GDPR Article 7 on the conditions for consent, it is up to the controller to demonstrate that the data subjected has consented AND, on top of that, not allowing refusal or withdrawal of consent means no freely given consent.

The WP29 guidelines also mention deception, intimidation, coercion or significant negative consequences as examples of detriment.

Valid consent: specific consent, specific purposes and purpose limitation

From freely given consent we move to a second element of valid consent: consent must be specific. This has everything to do with that previously mentioned crucial notion of personal data processing purposes.

On top of being legitimate the purpose of processing needs to be specific. This certainly touches upon elements we mentioned in the scope of freely given consent. Just think about the notion of granularity and how, if the processing purpose is not specific enough, the data subject can consent to purposes he or she might not have consented to if the purpose(s) were specific.

When the purpose of the data processing activity for which consent has been given has changed, reconsenting is required. When several operations serve the exact same purpose, consent should cover all processing activities carried out for the same purpose or purposes

GDPR Article 6 on the lawfulness of processing personal data emphasizes the fact that processing can only be lawful, in case consent is chosen as a lawful basis, if the consent relates to one or more specific purposes.

The first paragraph of GDPR Article 5, on the principles relating to the processing of personal, also emphasizes the concept of purpose limitation.

Although this isn’t strictly related to consent as the legal ground for lawful processing but to all personal data processing it of course fits in the need to be specific. Essentially purpose limitation means just what it says: the purpose needs to be limited and clearly known when, in the scope of this article, the data subject’s consent is sought. You also can’t just change it afterwards like that. Finally, the processing itself must happen in a way that is compatible with the specific purpose.

This also means that, when various data processing operations serve the exact same purpose consent may be given to these various operations the WP29 emphasizes, referring to Article 5 which also states that personal data have to be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes and to GDPR Recital 32 which is even clearer about this: “Consent should cover all processing activities carried out for the same purpose or purposes. When the processing has multiple purposes, consent should be given for all of them”.

There are two exceptions with regards to purpose limitation: 1) in the scope of where the processing for a purpose other than that for which the personal data have been collected is not based on the data subject’s consent (GDPR Article 6, paragraph 4) which doesn’t matter in the context of our article as we’re covering consent and 2) in the scope of personal data processing for archiving, scientific, historical or statistical purposes (GDPR Article 89). We cover these separately in our article on the principles regarding the processing of personal data.

Back to consent and specific consent. You might have noticed the use of the term ‘explicit’. Explicit pertains to the purpose of the data processing operation here. It isn’t the same as explicit consent; however it is once more (on top of initial drafts of the GDPR text) a token of how tin the line can be.

For the WP29 specific consent needs to be seen in the context of specific purpose(s), the choice data subjects have regarding each purpose and the guarantee that a data subject has as degree of control and transparency (another important concept as we’ll see).

Specific consent is also closely linked with the element of informed consent, which comes next, and as said with the requirement for free consent or freely given consent and for granularity.

- The link with informed consent is clear: if the data subject isn’t informed in a clear and specific way about the specific purposes then there can’t be explicit consent.

- The link with freely given consent then becomes clear as well, just as the fact that with granularity for each specific different purpose specific consent is needed.

Last, but not least, as a consequence of all the above: if you have consent for a specific purpose and want to process data for a new purpose consent needs to be asked again as the explicitly given consent no longer applies.

Informed consent: information as a duty and a right with a list of information to be given in the context of transparency

So, next a look at informed consent which, as mentioned overlaps with both freely given and specific consent, yet is mentioned as an element of valid consent as such too.

Informed consent and information-related principles

GDPR compliance does not equal transparency, fairness, lawfulness, integrity and accuracy. However, these principles are enshrined in the Regulation and with informed consent we are in the context of these principles, mainly but not solely, transparency.

If consent needs to be freely given, relating to a specific purpose and in line with all the other elements of consent, then it’s relatively easy to see that the data subject must be informed in a clear and transparent way before consenting to anything at all.

This doesn’t only apply to information that enables informed consent making true choice possible, it also goes for information regarding the rights data subjects have in our consent context, with the withdrawal of consent being the main one.

Let’s look at what the GDPR says about informed consent, on top of previously mentioned Articles and Recitals.

Providing information to data subjects prior to obtaining their consent is essential in order to enable them to make informed decisions, understand what they are agreeing to, and for example exercise their right to withdraw their consent (WP29 consent guidelines)

GDPR Recital 42 points to the requirement for the data controller to demonstrate that the data subject has given consent. Moreover, safeguards must ensure that the data subject is clearly aware of the fact that consent is given and to what extent it is given. This is particularly mentioned in the ‘context of a written declaration on another matter’ as is also stated in GDPR Article 7.

However, the fact that the declaration of consent should be pre-formulated by the data controller in an intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language (and that it should not contain unfair terms) is recognized as a controller duty. And that comes with specific information requirements that at the very least should be present and should be communicated.

GDPR Recital 42: “for consent to be informed, the data subject should be aware at least of the identity of the controller and the purposes of the processing for which the personal data are intended”.

GDPR Recital 78 clearly mentions transparency with regard to the functions and processing of personal data as one of the examples of technical and organizational measures the controller needs to foresee in order to be able to fulfil his duty of demonstrating compliance (along with others such as pseudonymization and those elsewhere in the GDPR such as DPIAs, adhering to an approved code of conduct and so on).

In other words: if that transparency lacks with regards to both the functions and processing (including gaining consent) then there is no compliance and it can’t be demonstrated.

Transparency is also mentioned in GDPR Article 12 in the scope of data subject rights. As we wrote in our article on data subject rights, the right to be informed is one of those rights. In fact, GDPR Article 12 starts by saying that “The controller shall take appropriate measures to provide any information referred to in Articles 13 and 14 and any communication under Articles 15 to 22 and 34 relating to processing to the data subject in a concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language”.

Informed consent: what information should be provided?

GDPR Article 13 dives deeper into the information which needs to be provided in case personal data are collected from the data subject, regardless of legal ground for lawful processing.

This information must be provided when the personal data are obtained and should, among others, at least mention:

- Identity and contact details of controller or controller representative.

- When applicable, contact details of the DPO (Data Protection Officer).

- Legal basis for processing AND PURPOSES of processing.

- Recipients or types of recipients of the personal data.

- Duration of storage of personal data or how that duration is determined.

- Notification regarding the right to access, rectification, erasure, restriction of processing, objection to processing and data portability.

- IF consent is the legal ground the fact that there is a right to withdraw it at any time, including the fact that when there is a withdrawal of consent this doesn’t impact the lawfulness of processing prior to it.

- The right to lodge a complaint.

- And more, which you can check out in that GDPR Article 13.

This doesn’t answer our question what information needs to be provided when informed consent is sought (and the list above is not exhaustive).

Most of the mentioned information duties clearly mention consent and are valid when consent is the legal ground. Moreover, some are clearly mentioned in the scope of fair and transparent processing.

However, the WP29 guidelines on consent have selected the following six types of information that are needed to obtain valid, informed consent:

- Identity of the controller.

- Purpose of each processing operation where consent is the legal ground.

- Data and type of data that will be collected and used through consent.

- The fact that there is a right to withdraw consent.

- Information regarding the use of data for decisions which are solely based on automated processing (including profiling), which is another one of those mentioned in GDPR Article 13.

- The fact that there is a possible risk of data transfers to third countries in some cases (also mentioned in Article 13).

While this list might seem less exhaustive than that in GDPR Article 13, this doesn’t mean that Article 13 isn’t valid of course but the information can be provided elsewhere as the WP29 mentions in its guidelines on transparency.

Do check out what the WP29 says on informed consent because on top of mentioning the type of information and the essential principles playing in the scope of informed consent there are ample guidelines on the form and the ways in which information needs to be provided to the data subject.

Unambiguous indications of consent and the meaning of a clear affirmative action in consent

Although there is a lot more to be said about consent (think about children, explicit consent which we covered separately, consent via electronic channels, the mentioned need to demonstrate consent, the right of withdrawal of consent, scientific research and far more) we’re wrapping this piece on GDPR and consent up with the last part of the definition of (valid) consent: the need for consent to be unambiguous and given by a statement or by a clear affirmative action.

We’ve tackled both the dimensions of “an unambiguous indication” and the element of action (no pre-ticked boxes, silence or inactivity) in the introduction and in the scope of freely given consent at the beginning of this article.

However, let’s look at what the WP29 guidelines on consent say about it. First of all, it needs to be obvious that consent has been given to a data processing activity. By definition this is almost the same as saying that the data subject must have taken a free, informed, specific and unambiguous action whereby there is no doubt possible at all.

The WP29 guidelines on consent refer to the predecessor of the GDPR (Directive 95/46/EC) which described consent as an “indication of wishes by which the data subject signifies his agreement to personal data relating to him being processed”. It isn’t too hard to imagine how this wasn’t always interpreted in the same way in several Member States and did lead to some confusions and backdoors, to say the least.

Let’s put it bluntly: many national supervisory authorities were already underfunded (and by the looks of it in some countries with the GDPR that isn’t about to rapidly change which of course comes with consequences regarding the enforcement of the GDPR) and you can’t really be much more vague than when speaking about an indication of wishes.

By explicitly adding the element of an unambiguous indication, mentioning the need of a statement or clear affirmative act and making pre-ticked opt-in boxes, as well as silence or inactivity on the part of the data subject, explicitly NO active indications of choice, this situation should clearly change with the GDPR, at least in theory.

Consent: distinguishable from other matters

Consent also needs to be distinguishable from other matters as specified in the second part of GDPR Article 7.

An example makes it immediately tangible: a company organized a marketing campaign to have people reconsent. It invited them at an event whereby a checkbox was added to reconfirm consent. This is not allowed as seeking consent, including a fresh consent to marketing, in such way was not distinguishable from the purpose of the campaign from the perspective of the data subject, namely an invitation to an event.

You can imagine ample similar scenarios whereby the seeking of consent or fresh consent could be tied to another, non-distinguishable matter.

GDPR Article 7(2): “If consent is given in the context of a written declaration which also concerns other matters, the request for consent must be presented in a manner which is clearly distinguishable from the other matters, in an intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language. If the data subject is asked to consent to something that is inconsistent with the requirements of the GDPR, that consent will not be binding”.

Top image: Shutterstock – Copyright: pashabo. GDPR Recital 43 image: Shutterstock – Copyright: Carlos Amarillo. Although our GDPR content has been carefully verified, we are not liable for potential mistakes and advice you to seek assistance in preparing for GDPR.