When Edward N. Lorenz, Professor of Meteorology, first talked about the butterfly effect in 1972 he had no idea how ‘his’ butterfly effect would be massively embraced in so many areas.

When he flapped his wings, talking about the idea, he sure set off a tornado himself. Lorenz essential talked about meteorology and – within that context – predictability when he wrote “Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?”.

It’s really an interesting read (PDF opens) – directly connected with what would become known as the chaos theory – and essentially about the potential impact that the small changes we can’t see in ‘sensitive systems’ (such as the atmosphere) can have a huge impact but make it virtually impossible to predict the what, how and interconnectedness of it all.

The complexity of predictability

Certainly when there are so many small impactful things that can cause huge change. What can we know, predict and possibly prevent if there are millions of butterflies flapping their wings at the same time?

We are at a point in time where we are overwhelmed with data – big and fast – and analytical possibilities, strengthened by artificial intelligence. The sheer computing power and ability to process data and turn it into actionable intelligence is tremendous and goes beyond anything that Edward Lorenz knew in 1972.

Still, we often make mistakes, especially when it boils down to people. A recent example we all remember: the total miscalculations and predictions regarding the outcome of the 2015 UK elections. However, when it comes to scientific data and also human behaviour we reach that point where ‘machines’ are redefining predictability.

[blockquote]Not the strongest survive but those who best adapt and, increasingly, pro-dapt.[/blockquote]Small changes with huge consequences – acting today for tomorrow

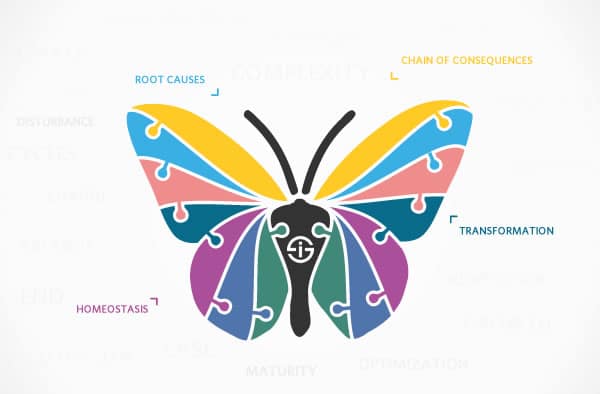

When looking at the popular interpretation of the butterfly effect, the potential huge impact of something very small, I can’t but think about the phenomenon of digital disruption and digital transformation. About how a sudden and apparently small shift in customer behavior can totally disrupt an industry. About how everything is connected and in our connected economy we work and live in ‘sensitive systems’. About how we need a state of ubiquitous optimization where I used the butterfly effect before.

We know how innovation and the actions we take today impact our tomorrow. And even if nothing in the end is really predictable we also know that small actions can make the world a better place. We don’t need data to understand that, gut feeling and common sense matter too. With data it all becomes easier.

Revisiting the butterfly effect: a continuous loop of transformation and adaptation

Transformation is essential to survival. It is and flapping those wings now and then indeed can cause a hurricane of opportunities for the future. It’s the essence of Darwinism. Not the strongest survive but those who best adapt and, increasingly, pro-dapt.

We face huge challenges regarding natural resources, climate changes, macro-economic shifts and the ways we conduct business throughout the entire ecosystem in which it resides. A connected ecosystem that looks a lot like an ecosystem in the biological sense – with butterflies.

It’s a sensitive ecosystem yet it needs butterflies flapping their wings. Because there is one thing regarding transformation that butterflies don’t have and we do.

A butterfly goes through several transformations before it becomes a butterfly and ultimately dies. We don’t have the luxury to stop transforming and revisiting and optimizing what we do in order to survive and thrive.

Disturbances and change are the only constant. And reality is not two-dimensional nor can be captured in loops and single causes as we often like to represent it in simple models as the “cycle” image above. It’s x-dimensional with x being what we don’t know. It’s non-linear like the customer reality. The puzzle is never finished and it shouldn’t be.

Top image: licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Central image purchased under license from Shutterstock.